TED and Tradition Chancel Arch, S. Maria dei Servi, Lucca, site of the TEDX event Chancel Arch, S. Maria dei Servi, Lucca, site of the TEDX event This past Saturday Lucca hosted its first TEDx event, Tempo Scaduto, or Time’s Up, organized around the theme of sustainability and the future of the planet. To their great credit, the first speaker was Daniela Murphy, a restorer based in Florence: conservation of culture is a critical part of the conservation of our environment in the broadest sense. Ms. Murphy spoke about lime—its chemical properties, its role in mural painting, its part in global sustainable construction. She made a call for artists and builders to use lime in their projects, whether in buon fresco painting or traditional masonry. We at the Tuscan Renaissance Academy have been advocates of lime-based painting and construction for decades. David Mayernik has been painting frescoes since he studied with the great restorer Leonetto Tintori in 1989. He worked alongside Tintori’s successors in the chapel of San Cresci in Valcava in the Mugello, they restoring an eighteenth-century Annunciation, he painting a new Crucifixion. Our integration of classical drawing and fresco technique is a unique approach to teaching principles and practice, orienting drawing toward its most important goal in the Renaissance, mural painting.

0 Comments

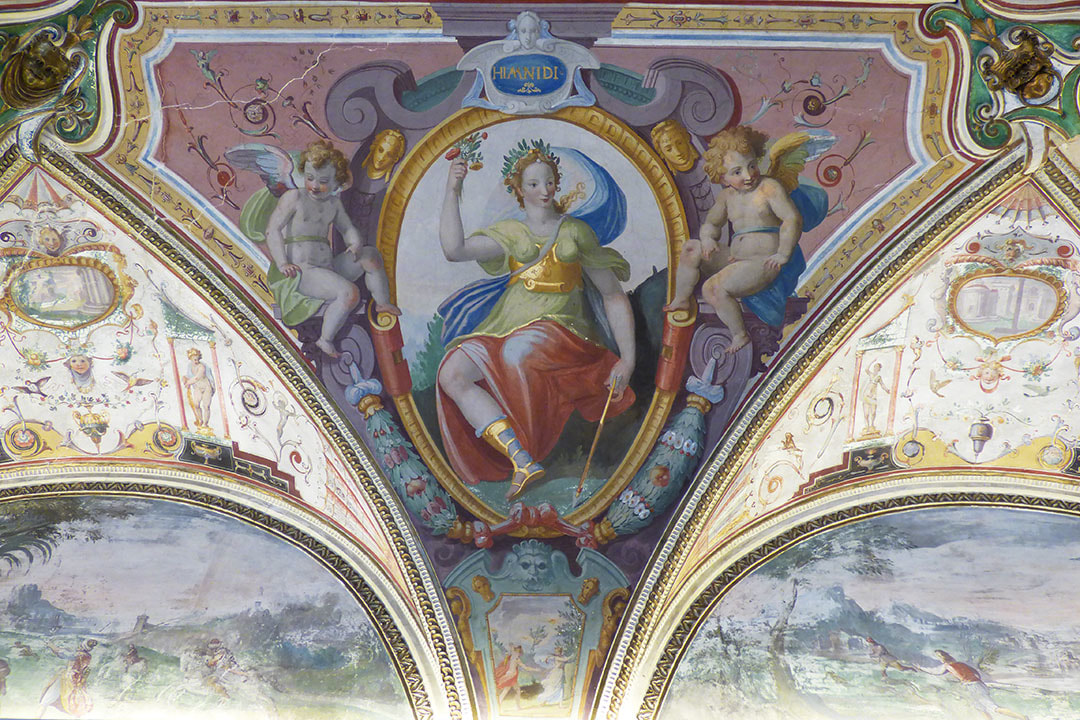

Himnidi, Villa Bottini Himnidi, Villa Bottini Like every Italian city, the technique of fresco painting survived in Lucca in one way or another from the ancient world into the Middle Ages. With the fifteenth century Lucca’s patrons could cast widely for artists to paint their churches and palaces. If perhaps the most famous work of art in the city is the precocious Renaissance sculpture of Ilaria del Carretto by Jacopo della Quercia, the city was simultaneously attracting artists from abroad whjle it nurtured a native school of painting. The church of S. Frediano is home to an elegant narrative cycle of the church’s patron saint by the Bolognese Amico Aspertini. In the apse of the same church is a delicate late fifteenth-century fresco of Angels Adoring the Eucharist. The sixteenth century saw the peninsula-wide dissemination of High Renaissance and Mannerist achievements, and Lucca’s wealthy patrons ambitiously commissioned cycles for their palaces and villas. The Palazzo Santini (now city government offices) has a ground floor loggia gracefully painted with grottesques, open to the surrounding streets. Unusually, Lucca has villas within its walls, its famous mural circuit enclosing areas that had previously been outside the walls, or suburbana. Villa Bottini is perhaps the most remarkable example, its main floor ceilings completely frescoed with cycles illustrating humanistic themes of the Arts, Virtues, etc. A team of artists led by the Sienese Ventura Salimbeni realized the complex cycle in brilliant colors and graceful figures intertwined with an advanced architectural armature. In the seventeenth century Lucca gave birth to the remarkable team of Giovanni Coli and Filippo Gherardi, who painted frescoes in the cathedral and San Paolino before going to Rome and creating their triumphant ceiling in the Palazzo Colonna. In the eighteenth century, Pompeo Batoni was perhaps Lucca’s most famous product, but he largely made his career in Rome after the significant altar painting of S. Caterina in the eponymous church of his native city. Later in the century the Lucca produced Stefano Tofanelli, who painted in S. Frediano and elsewhere in a sophisticated neoclassical manner infused with Renaissance principles. With him in Rome was his fellow Lucchese Bernardo Nocchi. |

AuthorsFederico Del Carlo Archives

October 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed