What Raphael Saw in FlorenceFilippino Lippi (who sent a painting to Lucca around the same time) was especially influential because of his interest in grotesque ornament (derived from what artists saw of Roman wall painting in buried chambers, or grotte, literally caves), which Raphael and his assistant Giovanni da Udine would exploit so spectacularly in Rome.

Our intensive Summer 2020 workshop will give you the skills to see and document the world in accurate perspectival drawing.

0 Comments

Day trip to Florence, Wednesday Florence is only a little over an hour by train from Lucca; and, not being a large city, but a rich one, it is easy to see a lot of things in a short time. Some highlights here (clockwise from upper left) are Palazzo Strozzi and the Verocchio show, Zecchi art supply shop, the cathedral works down the street from Zecchi, and the atrium of Ss. Annunziata with frescoes by Pontormo, Rosso, and their teacher Andrea del Sarto Day trip to Florence, Wednesday Florence is only a little over an hour by train from Lucca; and, not being a large city, but a rich one, it is easy to see a lot of things in a short time. Some highlights here (clockwise from upper left) are Palazzo Strozzi and the Verocchio show, Zecchi art supply shop, the cathedral works down the street from Zecchi, and the atrium of Ss. Annunziata with frescoes by Pontormo, Rosso, and their teacher Andrea del Sarto Some highlights from week one of Summer 2019. Lucca is a unique base for the study of Renaissance art and architecture principles, with great buildings and works of art by Tuscan artists, a history of producing its own artists (especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries), and a variety of cultural and natural resources within a short distance...

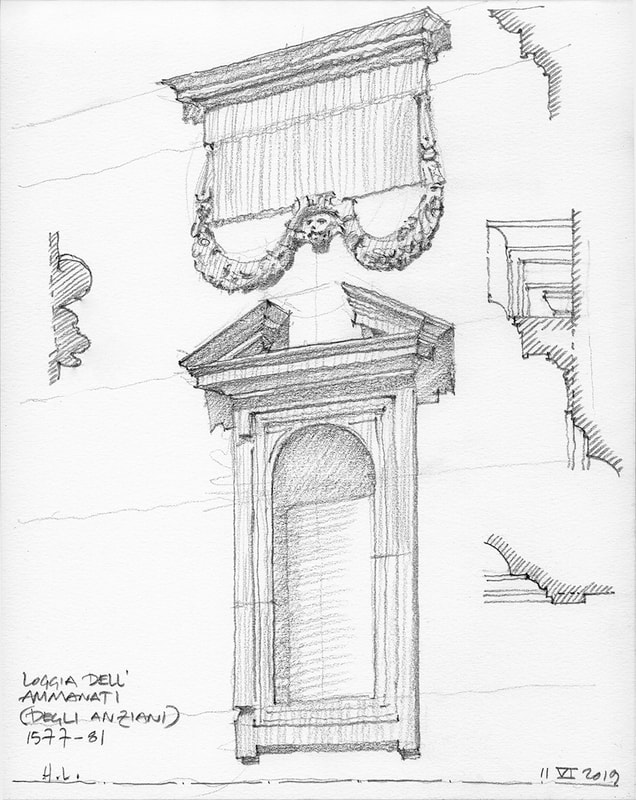

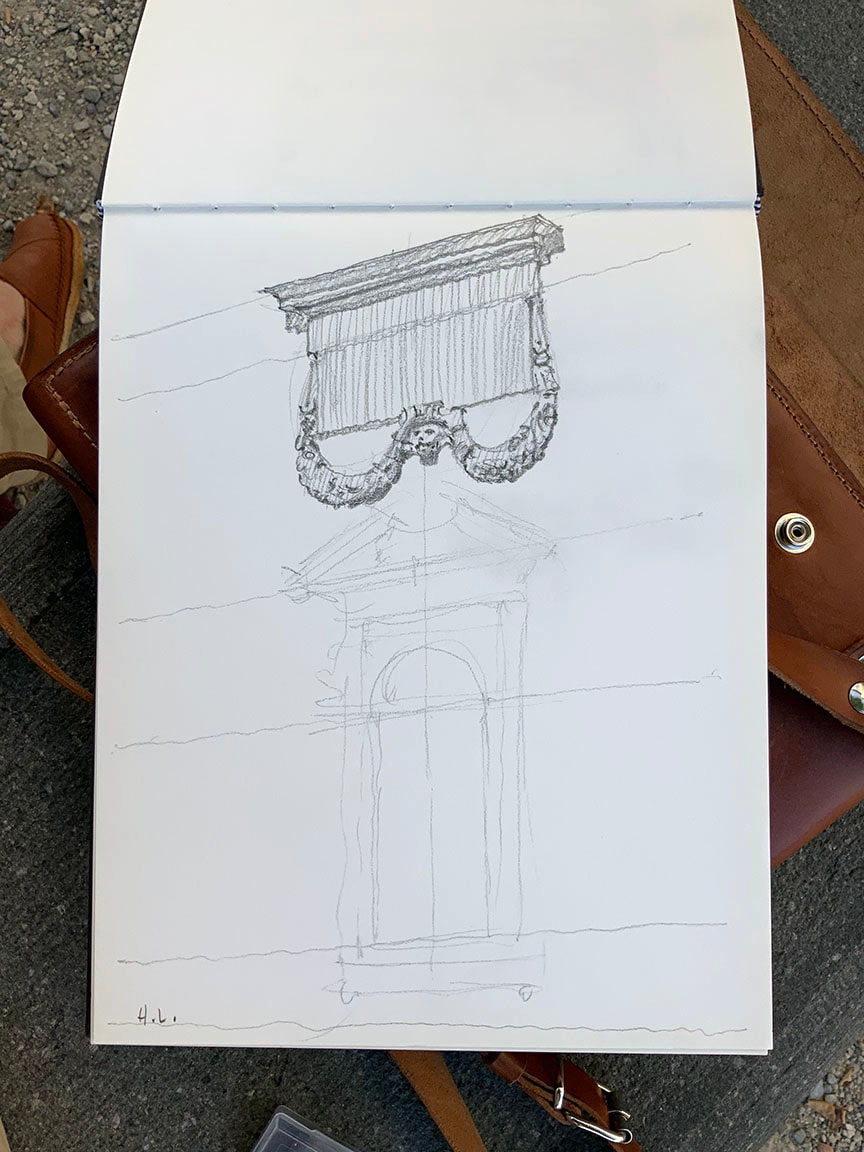

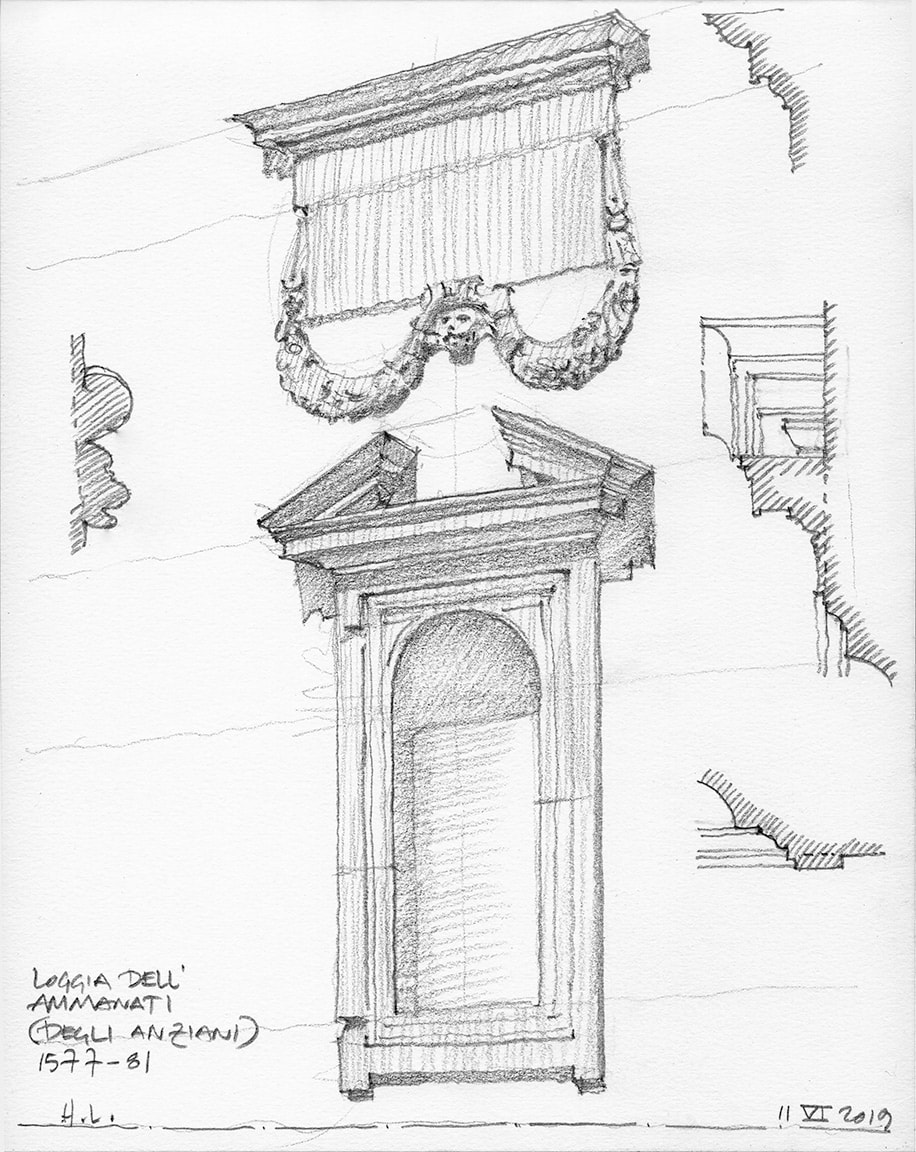

Loggia dell'Ammannati This beautiful summer morning we drew a part of the Palazzo Ducale complex, the late sixteenth-century loggia by Bartolomeo Ammannati. Ammannati was a remarkable figure of the late Renaissance, having trained under Bacio Bandinelli in Florence, then working under Jacopo Sansovino in Venice (particularly on the sculptures of the Libreria Marciana on the Piazzetta di S. Marco). A sculptor by formation and talent, he found his way to architecture in the Rome of Julius III, particularly at the Villa Giulia but also the Palazzo di Firenze (formerly Medici), before returning to Florence. There he practiced as both sculptor (Neptune fountain, Piazza della Signoria) and architect (Palazzo Pitti); he was Michelangelo’s executor for the Laurentian Library stair. Drawing a part of one of the façade bays in two-point perspective, we were concerned to both delineate and shade the subject accurately from our position on a bench in the Piazza Napoleone. Needless to say, we did not use sight-size, rather propping the sketchbook on our laps and constantly looking from subject to drawing, training the memory as well as the hand. After the view (about half an hour) we quickly documented the molding profiles. On site drawing of architecture is both documentary and analytical, and Renaissance artists and architects dissected buildings as well as bodies. Follow the progress in the images below. Can you name the sequences of molding profiles? Note how Ammannati varies the sequences of moldings between the upper and lower cornices. Also note how the plane of the niche is recessed with respect to the plane of the stucco wall.

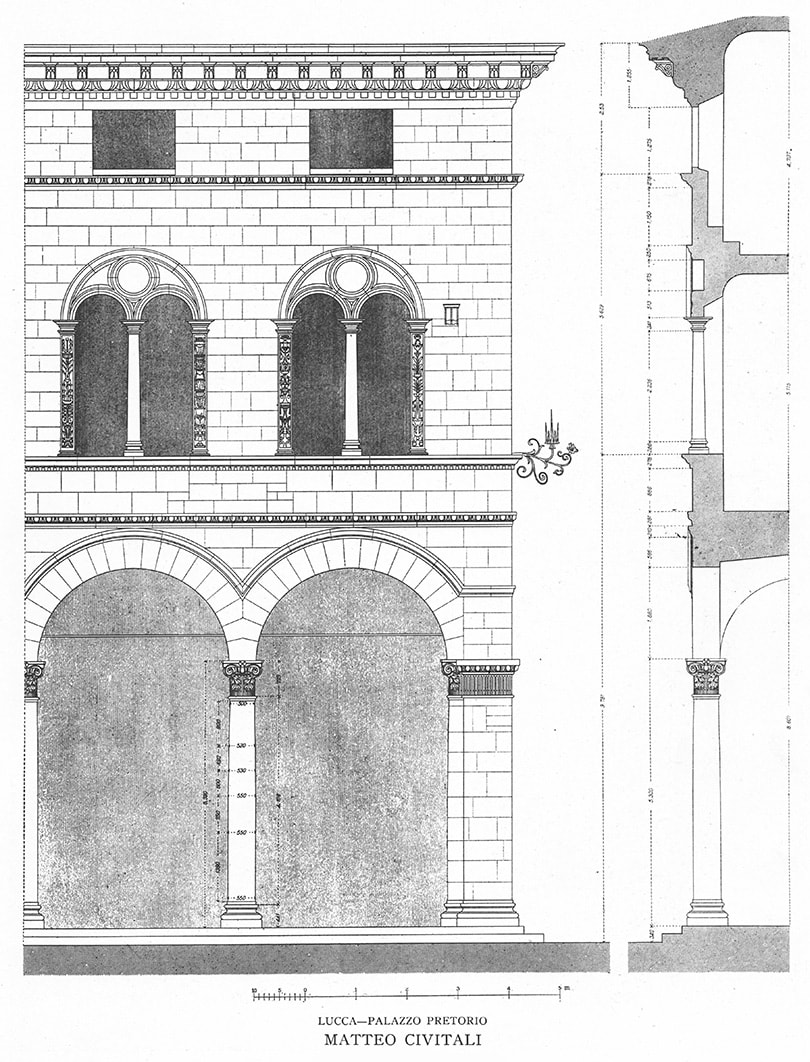

We speak of The Renaissance, but in Italy one could more accurately talk about a Florentine Renaissance, a Venetian Renaissance, a Milanese Renaissance, etc. While there were ideas and currents that wove through and united all of those places, local traditions, artists, and architects ground their work in their particular place. This is more true of the fifteenth than the sixteenth century, when the earlier work was still transitional from vestiges of medieval art and architecture. Lucca had its own iteration of the Renaissance, sustained by local patronage of local artists—including transplanted “foreigners” like Matteo Civitali, whose roots were in the Veneto (as his name suggests). While Lucchese patrons would occasionally commission a prestigious artist from elsewhere in Tuscany--Filippino Lippi for S. Michele, Fra Bartolomeo in the Cathedral, and of course Jacopo della Quercia for the tomb of Ilaria del Carretto originally in S. Francesco—they mostly relied on indigenous talent, in part to sustain their native taste. The same, of course, happened in Florence and Venice.

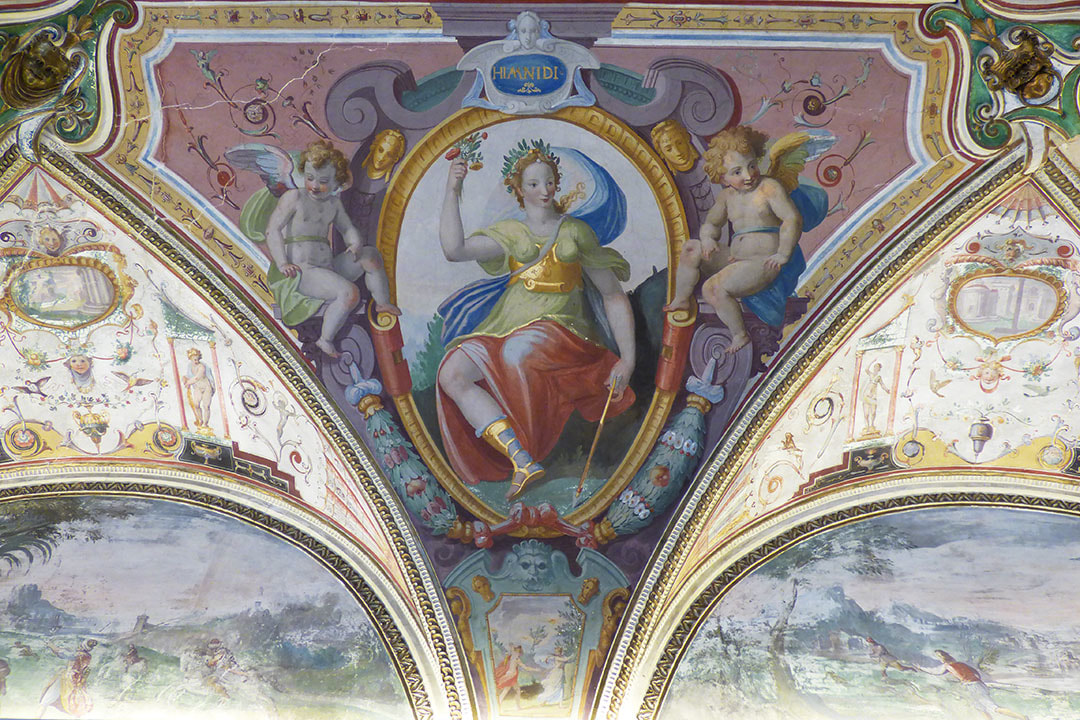

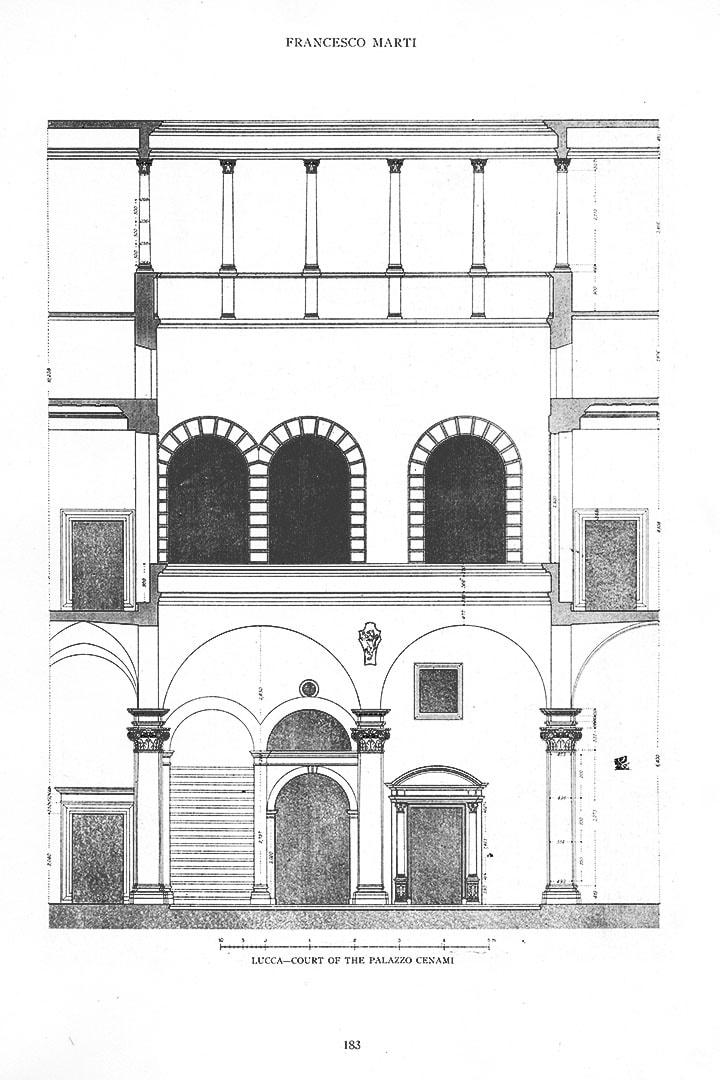

Carl von Stegmann and Heinrich von Geymüller’s documentation of Tuscan Renaissance architecture in two volumes features Lucchese buldings in each volume. For the early work in volume one there are photographs and drawings of the Palazzo Pretorio (which they attribute to Civitali), Palazzo Bernardini and Palazzo Cenami, and S. Paolino by Baccio da Montelupo. Our instruction in drawing uses these exemplary buildings as models for the mastery of perspective and visual measuring, and as paradigms in their own right. One can learn the canonical language of classical drawing while also being alive to the local dialects.  It might be said a certain fetishizing of the finished drawing has accompanied the recovery of Realist representational techniques in the last couple of decades. Not in and of itself a bad thing, being able to accurately represent what one sees is a necessary (if insufficient) condition for a rebirth of representational art. But if we think drawings that imitate black and white photographs are ìn some way “traditional,” or “classical,” we are misguided. Because drawing was, in the Old Master tradition, almost always a means toward an end. And that end was something more substantive, permanent, and often public. Murals, sculpture, altar paintings are what sponsored drawing as a preparatory art, one involved in both the invention of a composition and the working out of the elements of that composition. Since drawing was rarely an end in itself, it was calibrated to be an efficient tool in this larger process. It had to be done in a relatively short period of time, it had to distil what was essential about what was being drawn, and it was meant as much to shape the memory of the artist as to add to his portfolio. Morevoer, without the model of photography to measure it against, a drawing was instead prized for its graphic grace, liveliness, andsprezzatura. The fact that it consisted of marks on paper was not contrary to this appreciation, it was in fact essential. Because in the mark the artist revealed his or her genius, intellect, and facility. Raphael is undoubtedly the paradigm of the classical artist, a model for centuries of aspiring classical painters. And while Raphael’s early drawings are meticulous, delicate, and refined, it was only after he experienced Michelangelo’s bravura draftsmanship that he developed that drawing style, mostly in sanguine, that would define the aspirational model of classical drawing. These sanguines of Raphael's–bold and delicate, economical and informative, composed of both a lively contour and descriptive hatching–are what we at the Tuscan Renaissance Academy hold up as ideals. Almost none of the great drawings of Raphael’s Roman period took more than an hour to produce. All are essential tools for the realization of powerful paintings or tapestries. And they require a different approach than what is often held up as academic drawing today. They are what informed the Carracci reform of painting in the early seventeenth century. TED and Tradition Chancel Arch, S. Maria dei Servi, Lucca, site of the TEDX event Chancel Arch, S. Maria dei Servi, Lucca, site of the TEDX event This past Saturday Lucca hosted its first TEDx event, Tempo Scaduto, or Time’s Up, organized around the theme of sustainability and the future of the planet. To their great credit, the first speaker was Daniela Murphy, a restorer based in Florence: conservation of culture is a critical part of the conservation of our environment in the broadest sense. Ms. Murphy spoke about lime—its chemical properties, its role in mural painting, its part in global sustainable construction. She made a call for artists and builders to use lime in their projects, whether in buon fresco painting or traditional masonry. We at the Tuscan Renaissance Academy have been advocates of lime-based painting and construction for decades. David Mayernik has been painting frescoes since he studied with the great restorer Leonetto Tintori in 1989. He worked alongside Tintori’s successors in the chapel of San Cresci in Valcava in the Mugello, they restoring an eighteenth-century Annunciation, he painting a new Crucifixion. Our integration of classical drawing and fresco technique is a unique approach to teaching principles and practice, orienting drawing toward its most important goal in the Renaissance, mural painting.  Himnidi, Villa Bottini Himnidi, Villa Bottini Like every Italian city, the technique of fresco painting survived in Lucca in one way or another from the ancient world into the Middle Ages. With the fifteenth century Lucca’s patrons could cast widely for artists to paint their churches and palaces. If perhaps the most famous work of art in the city is the precocious Renaissance sculpture of Ilaria del Carretto by Jacopo della Quercia, the city was simultaneously attracting artists from abroad whjle it nurtured a native school of painting. The church of S. Frediano is home to an elegant narrative cycle of the church’s patron saint by the Bolognese Amico Aspertini. In the apse of the same church is a delicate late fifteenth-century fresco of Angels Adoring the Eucharist. The sixteenth century saw the peninsula-wide dissemination of High Renaissance and Mannerist achievements, and Lucca’s wealthy patrons ambitiously commissioned cycles for their palaces and villas. The Palazzo Santini (now city government offices) has a ground floor loggia gracefully painted with grottesques, open to the surrounding streets. Unusually, Lucca has villas within its walls, its famous mural circuit enclosing areas that had previously been outside the walls, or suburbana. Villa Bottini is perhaps the most remarkable example, its main floor ceilings completely frescoed with cycles illustrating humanistic themes of the Arts, Virtues, etc. A team of artists led by the Sienese Ventura Salimbeni realized the complex cycle in brilliant colors and graceful figures intertwined with an advanced architectural armature. In the seventeenth century Lucca gave birth to the remarkable team of Giovanni Coli and Filippo Gherardi, who painted frescoes in the cathedral and San Paolino before going to Rome and creating their triumphant ceiling in the Palazzo Colonna. In the eighteenth century, Pompeo Batoni was perhaps Lucca’s most famous product, but he largely made his career in Rome after the significant altar painting of S. Caterina in the eponymous church of his native city. Later in the century the Lucca produced Stefano Tofanelli, who painted in S. Frediano and elsewhere in a sophisticated neoclassical manner infused with Renaissance principles. With him in Rome was his fellow Lucchese Bernardo Nocchi.  Federico and David in Piazza S. Michele; photo by Brette A. Jackson Federico and David in Piazza S. Michele; photo by Brette A. Jackson by Brette A. Jackson What is a great thing to do in Lucca on a beautiful, sunny summer day? Make surveys of several Renaissance palazzi in the historical city center. In June, David and Federico set out together and created measured drawings of two principle Renaissance edifices: the Palazzo Pretorio, which is the city’s former seat of the Podesta(the chief magistrate in a medieval Italian municipality), and the Santissimo Sacramento, a small chapel that is part of Lucca’s cathedral, San Martino. Architectural surveying is an empirical method of drawing that offers the designer the opportunity to analyze a building’s proportion and structure by eye; this can be accomplished by either using one-point perspective or elevation. Working in tandem, David and Federico discussed the essential elements of each building (e.g. the length of the columns, the arches, etc.) and then standing at a distance that allowed them a full view of both the palazzo and chapel, they each drew areas of each structure using their preferred method of executing their renditions: for instance, Federico drew an elevation to use a more analytical approach by figuring out the perspective by drawing directly from sight, while David uses a more precise and mathematical approach of applying one-point perspective. There is really no better exercise in comprehending the general principles of perspective and architectural design than standing in from of a well-designed building, breaking down its parts, and then drawing it directly from sight. Think of it as drawing a live model; capturing all of their contours and distinct features, while also understanding the constant that the human body is symmetrical—thus, two eyes, arms, legs, feet, etc. Lucca is a small city with a large personality; it is both easy and pleasant to apprehend its streets, edifices, and civic art. The summer offers long, sunshine-filled days that will offer you the opportunity to copy and emulate architecture and art in a lovely Tuscan Renaissance city with two professors whose passion, talent, and love of Lucca promise to offer a challenging, engaging, and artistic summer. Come and experience the art and culture of a viable city whose inhabitants harmoniously coexist with its past: The Tuscan Renaissance Academy would like to open the door to a portal that will teach you about the significance of the art and architecture of the Renaissance: its significance to the past, and it relevance to the present.  This is the first post of our ongoing activities at the Tuscan Renaissance Academy. Over the summer of 2018 we visited some of Lucca's important Renaissance buildings to show how the period's drawing techniques, both perspectival and orthographic, can be used to document and understand these remarkable structures. We also posted on this site an idea for reconstructing the garden of the fifteenth-century Villa Guinigi (see photo above), the city's art museum. Our future blog posts will show Federico and David at work and explain our principles and pedagogy. Check our our Summer 2019 course offering, and Welcome. |

AuthorsFederico Del Carlo Archives

October 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed