|

We speak of The Renaissance, but in Italy one could more accurately talk about a Florentine Renaissance, a Venetian Renaissance, a Milanese Renaissance, etc. While there were ideas and currents that wove through and united all of those places, local traditions, artists, and architects ground their work in their particular place. This is more true of the fifteenth than the sixteenth century, when the earlier work was still transitional from vestiges of medieval art and architecture. Lucca had its own iteration of the Renaissance, sustained by local patronage of local artists—including transplanted “foreigners” like Matteo Civitali, whose roots were in the Veneto (as his name suggests). While Lucchese patrons would occasionally commission a prestigious artist from elsewhere in Tuscany--Filippino Lippi for S. Michele, Fra Bartolomeo in the Cathedral, and of course Jacopo della Quercia for the tomb of Ilaria del Carretto originally in S. Francesco—they mostly relied on indigenous talent, in part to sustain their native taste. The same, of course, happened in Florence and Venice.

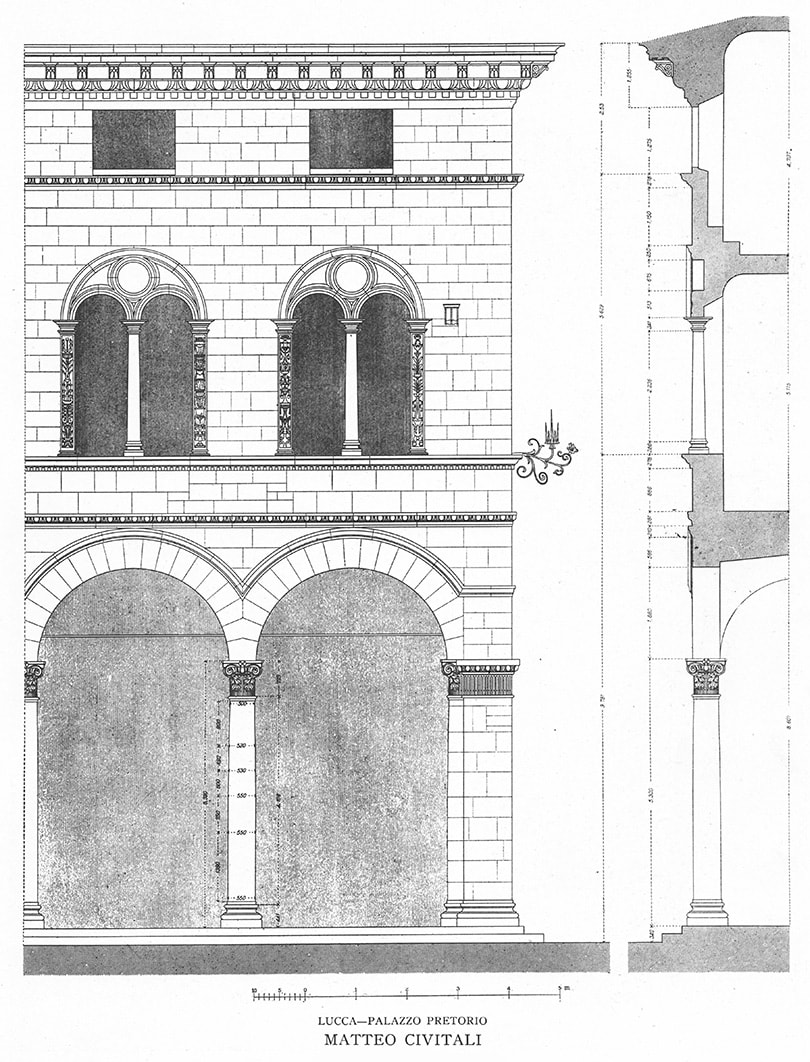

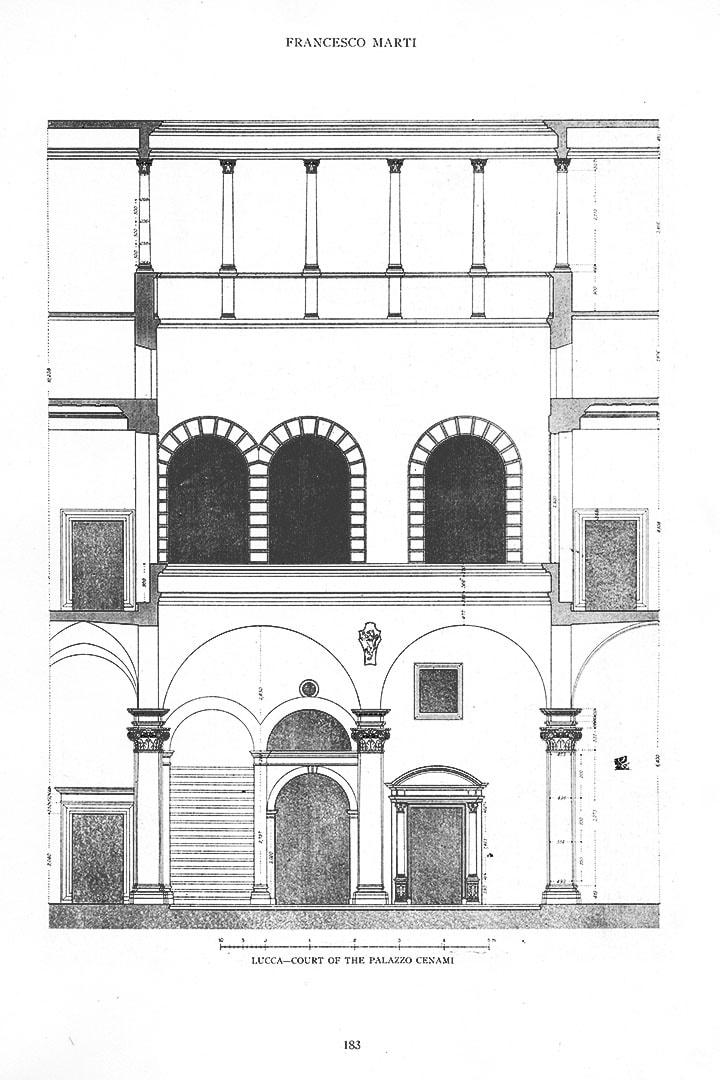

Carl von Stegmann and Heinrich von Geymüller’s documentation of Tuscan Renaissance architecture in two volumes features Lucchese buldings in each volume. For the early work in volume one there are photographs and drawings of the Palazzo Pretorio (which they attribute to Civitali), Palazzo Bernardini and Palazzo Cenami, and S. Paolino by Baccio da Montelupo. Our instruction in drawing uses these exemplary buildings as models for the mastery of perspective and visual measuring, and as paradigms in their own right. One can learn the canonical language of classical drawing while also being alive to the local dialects.

0 Comments

|

AuthorsFederico Del Carlo Archives

October 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed